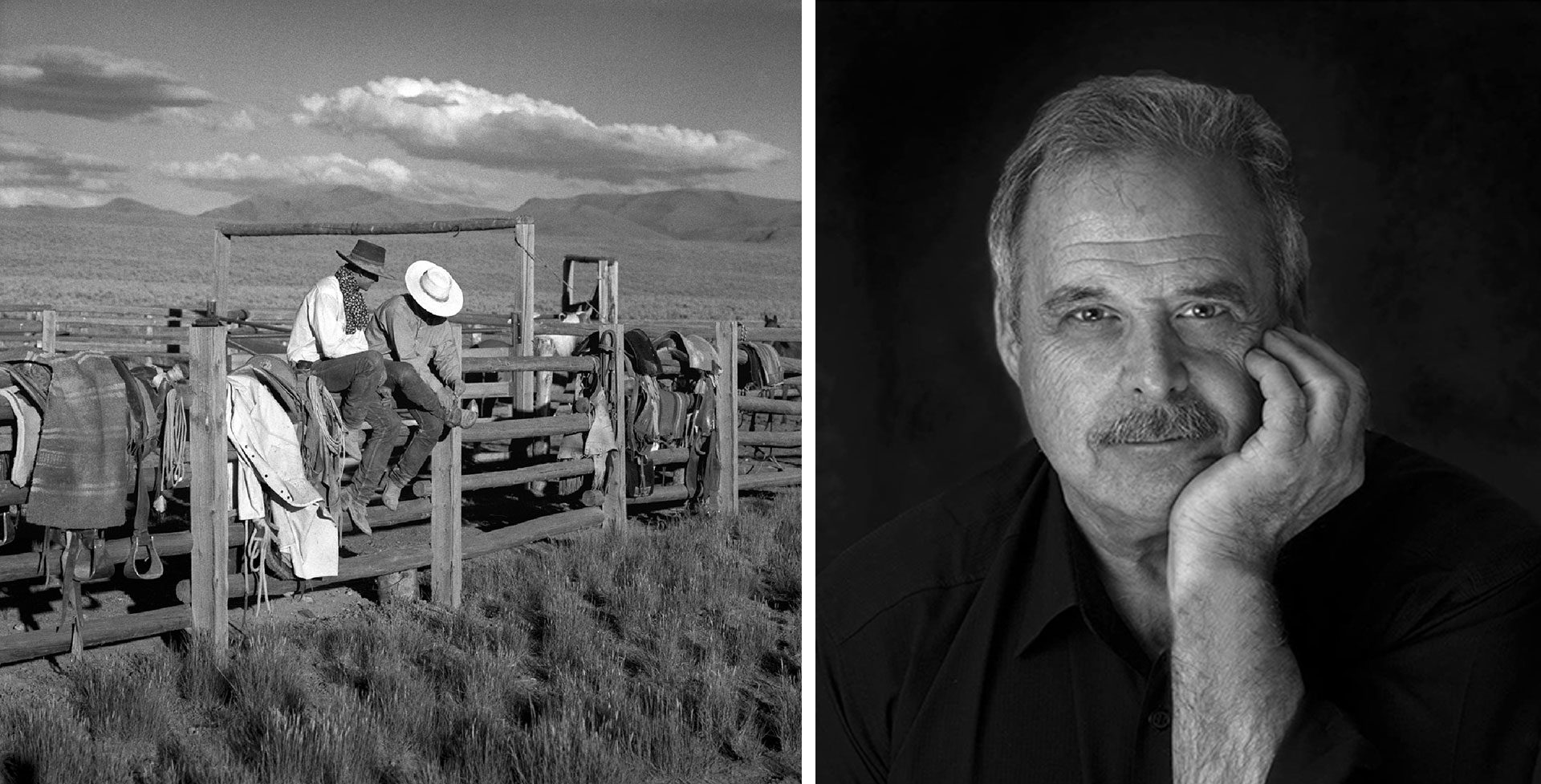

Photographer Adam Jahiel has had a varied professional career. He has worked for the motion picture industry, adventure projects, most notably as the photographer for the landmark French-American 1987 Titanic expedition. His work has appeared in most major U.S. publications, including Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, National Geographic Society and others.

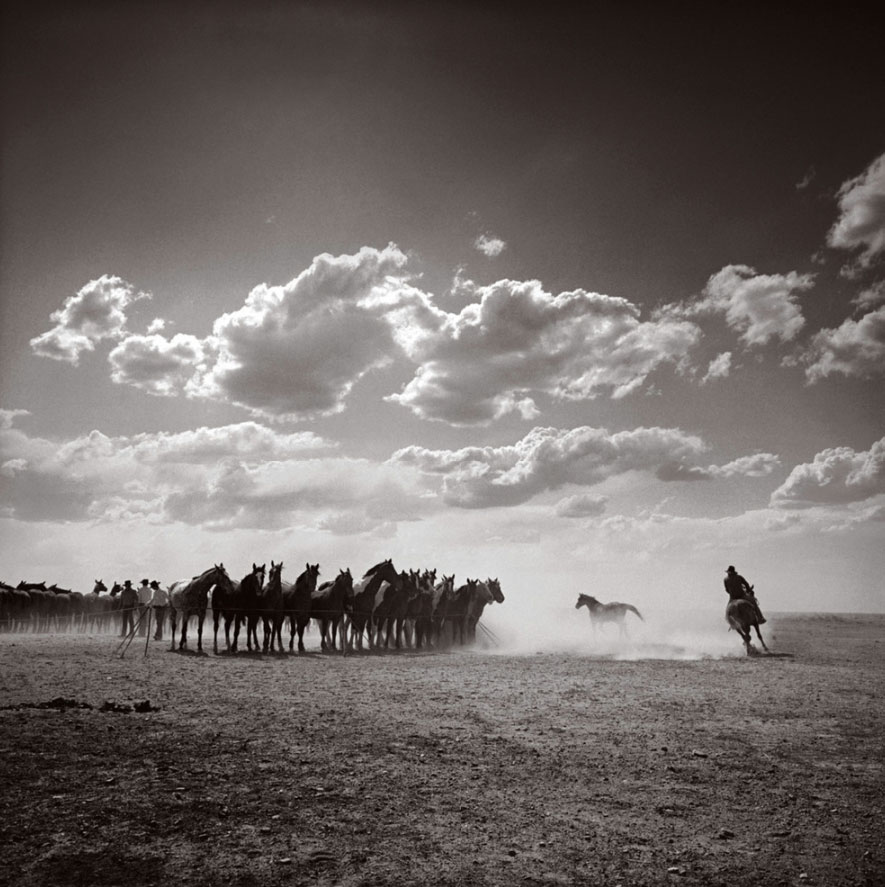

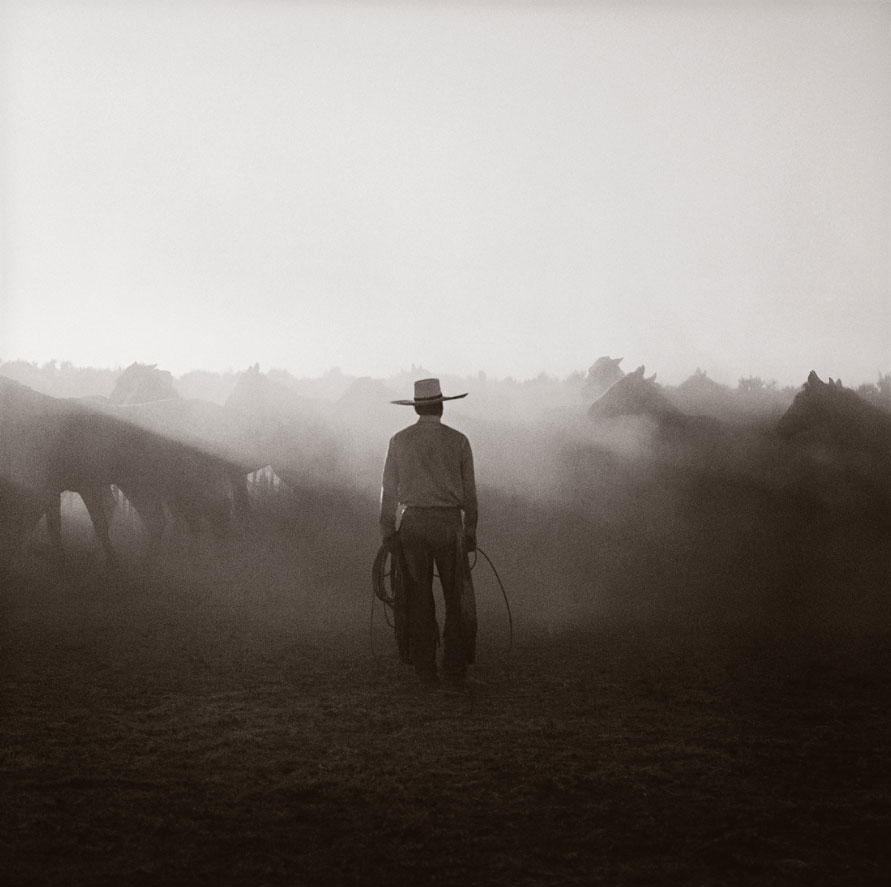

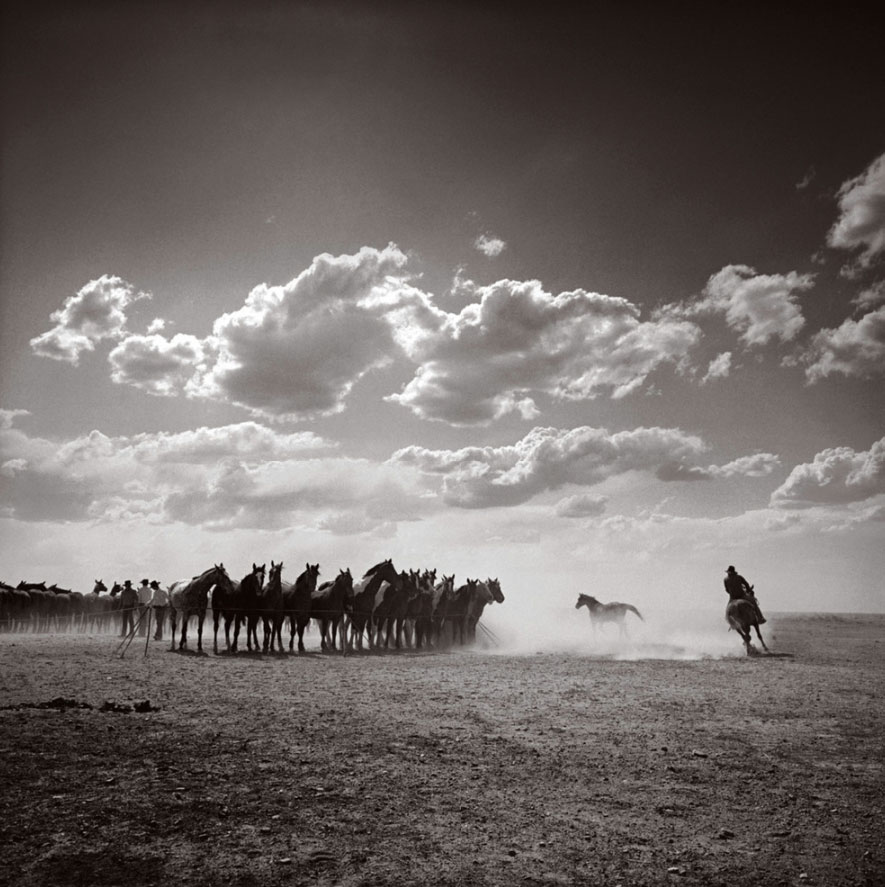

For years, Jahiel has photographed the cowboys of the Great Basin, perhaps one of the most inhospitable regions of the already rugged West. These people represent one of the last authentic American subcultures, one that is disappearing at a rapid rate. Cowboying as an art form is almost obsolete; still, the cowboys hang on, with a ferocious tenacity. Jahiel tries to reflect those sentiments in these photographs. These cowboys aren’t “remade” into a Hollywood image. Instead, they are “found” images, in keeping with the spirit of authenticity that permeates the best keepers of this tradition.

You studied commercial photography, but you also studied photojournalism. Did that inform your ability to observe and almost act as a journalist, in addition to a photographer?

I think the big difference is that you could work on something, take a bunch of Polaroids, shut the lights off, come back the next morning, and fine tune. With photojournalism, you learn to think on your feet because you don’t have the luxury of time. It’s a whole art. You have to make do with what you have, no matter what the situation is. I think that’s really helped me out a lot. I mean, I think I’m a photojournalist at heart.

But, I read that taking technically perfect photos is very important to you. Do you think it’s that old Picasso saying about how you have to learn the rules to break the rules?

Absolutely. When I look at photography that really trips me, I see a coming together of great technique and great storytelling. You can have one without the other, but the closest to perfection you can get is the art and the science. You have to hold both blades.

When it came to shooting the Great Basin Cowboys, I know the project was born when you were sent on assignment to shoot the famous rodeo bull for The Sacramento Bee, but how did you get a foot in the door? Was it difficult to break into this group or is that a stereotype?

I corresponded with the cow boss, who are often ranchers, to get permission to come out to the ranch. When I got to the ranch, I realized how important this opportunity was. I thought, “Keep your eyes open and your mouth shut and whatever you do, ride last, eat last, drink last, don’t do anything until you’re asked to do it and just minimize your presence as much as possible.” Somehow that worked, because the last day, I told the cow boss that I was going to leave and he just kind of nodded and rode off. A few minutes later, he circled back around and said, “If you want to shoot at any other ranches, you can use me as a reference.” To this day, I feel like that’s one of the biggest accolades I’ve ever received.

Every place I went, I was more at ease and I knew more of their story. After a while, I became the messenger, letting everybody know who got married, who got divorced, who quit. I started to see the same faces on different ranches and so I’d walk into a place and realize that I knew half the crew and the other cowboys picked up on it. It slowly built up to the point where I could pick up the phone and they knew I wasn’t a threat.

Did you already know how to ride a horse, or did you have to study their work, so you could blend in and also know what to expect in order to get the right shot?

I grew up doing some riding. I brought my own saddle, my own gear and my own bed roll, so all I needed was one of the horses. I came as prepared as I could be but I also remained as humble as I could be. That combination worked and it didn’t take long to get into their whole style of riding and roping and living and weird hours where you’re getting up at three or four in the morning and everything is pitch black outside and there’s stars in the sky and you have breakfast and by the time you’re saddling your horse, it’s just barely getting light. It was a lot to get used to, but I fell into it.

When you’re out there and in the moment, do you snap photo after photo or do you wait for the right moment?

On that project, I shot film on a Mamiya six 200 quarter camera, so you get 12 shots per roll. You have to be really judicious and do a lot of thinking and watching and anticipating what’s going to happen.

I didn’t want to be inundated with developing hundreds of rolls of film when I got home. There’s something about that 12 shots per roll; you have to make every shot. It’s about as hands-on as you can get as a photographer because you’re loading and you’re shooting and you’re unloading and you’re processing and you’re printing. you have that human personal touch all the way through the process.

You often shoot in black and white and, specifically for this work, in a square format; why is that your preference?

I’ve always been in love with black and white, and I know my dad shot a lot of square two-and-a-quarter film. I think the simpler, the better; the less things you have to do, the more you can react and create images. For me, my photography is just my reaction. You get this gut feeling and then it goes to your shutter finger. I just try to shoot what I feel and I’m not very analytical. With the square format, you just put four lines around your subject and take the picture. In a situation where things are happening fast and you don’t have time to set up a camera on a tripod, I found it to be the perfect tool. There’s so much texture and detail in the light and the dust and the leather and the faces and the clothes—it tells such a great story and the medium format pulls it all in.

Obviously, you hear about this type of cowboy slowly disappearing. How has that impacted how you think about your work and what evidence you’re leaving behind?

The last-of-the-breed type stories have been around probably forever. I didn’t start out saying, “I’m going to capture a moment in history,” but having said that, the years I spent photographing on these ranches were the heyday. I think the Cowboys will be around and the beef industry will last a really long time but when I was photographing, there were old timers and career Cowboys. Now you see more young men that are veterinary or agriculture students who come from a ranching background and want to cowboy for a couple years to have the experience. You just don’t find a whole lot of old timers around anymore and they have the great faces and the great stories and are just so interesting to be around.

What has been the cowboy’s reactions to your photographs of their way of life, and the attention your work has received? I can imagine that’s an interesting part of shooting people.

People are always really thankful that I am accurately portraying their lifestyle and what they do. I don’t over romanticize the “cowboy” thing; I try to work in more of a straight-forward documentary style. I think there is a real romance but the romance is not what people think it is. It’s a beautiful part of the country and it feels good and the light’s good and the country’s good and you get up in the dark and start riding and the temperature goes up and you appreciate everything about it. They take a lot of pride in their work and their culture. If someone comes along and portrays it in an honest manner, they’re very happy.