Jonathan Swanz has been crafting art for over 20 years developing facility in a variety of media with a focused refinement in the glass techniques of blowing, casting, carving, and sculpting. He has worked with exceptional artists across Europe and the US, including Paris, Venice, Copenhagen, New York, Seattle, and Chicago. He has completed extensive commercial and residential architectural commissions nationwide and has pieces in the permanent collections of The Hawaii State Art Museum Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children and Park Lane of Honolulu, HI, 21C Museum and Hilliard Lyons of Louisville, KY, the Headley Whitney Museum of Lexington, KY, and PNC Bank of New York, NY.

His studio practice continues to explore parallels in the energetic and social nature of materials and humans by investigating state change and energy transfer through the manipulation of molten glass, digital media, performance, and architectural installations.

What is it about glass blowing that captivated you then, and has also continued to inspire you over the years?

What I have realized is that the crafts that are more physical, there’s an embodied problem solving that I really enjoy. Your whole body is part of the problem solving. It’s not just the theoretical piece in my mind, but the physicality of it that really drew me into it. And then I just kept making and studying, taking advantage of different opportunities to work with different masters and artists. I worked in a production glass studio and the summers while I was in college, I studied art and philosophy at a liberal arts. Then I got a job working for this production glass blower and later for an architectural glass studio and that’s when I started thinking about larger-scale projects. And then when I came back from Europe, I started my own studio. That’s when I took on some of my first lighting projects.

How did you go about planning this tree?

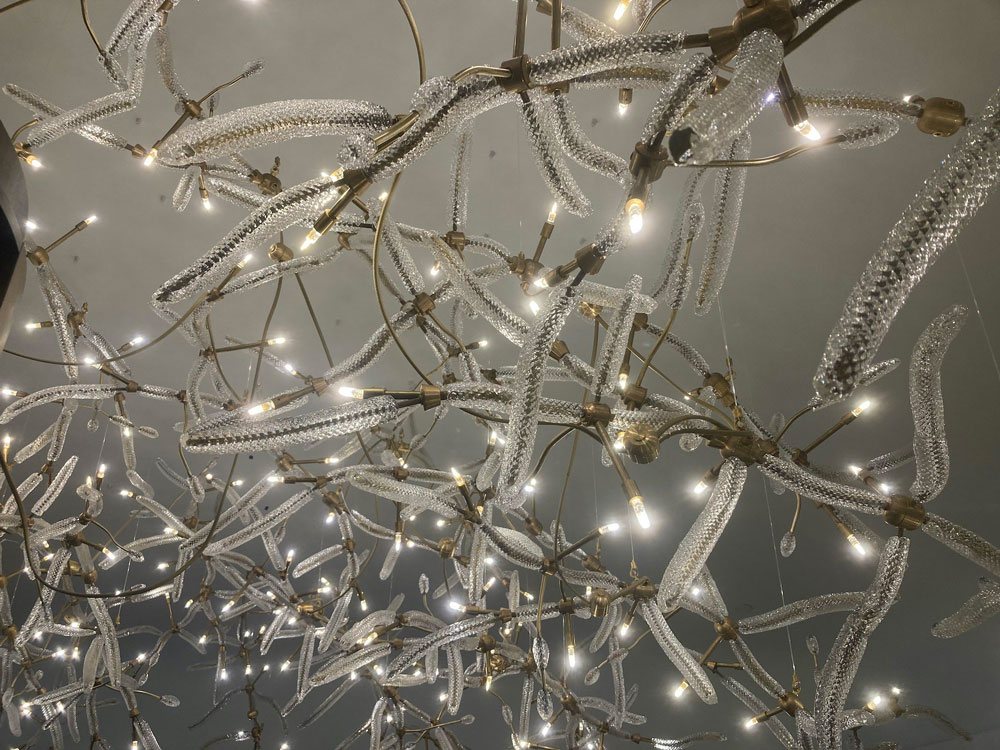

One of the things that I really, truly believe is that if there’s not a moment in a project where I’m panicked, then I’m not pushing myself. That happened a few times with this project because we designed it from the ground up. Simeone Deary came up with the concept of a fantastical glass tree but there wasn’t any kind of nuts and bolts or mechanics. I’ve never seen anything like it, and it hasn’t been translated into any other means, except for this lighting concept, which I think of as being a modular and scalable lighting concept inspired by Banyan trees.

The whole design went through so many iterations and I made models all along the way, trying to figure out the engineering. Initially the branches were going to come out from the trunk and that would’ve been cantilevered. That was going to be structurally tricky with the ceiling and load bearing points. At some point it hit me that if I can make individual branches, this is where it becomes modular and scalable.

“The inspiration behind the bespoke, glass sculpture at the PGA Golf Club and Spa central bar was influenced by the mighty Banyan tree and the symbol that this monument represents to the city of Palm Beach Gardens – the home of PGA. As the tree was originally planned as the city’s central touchstone, so this glittering beacon sits at the center of the effervescent lobby bar and engaging lounge.”

Lisa Simeone, Owner, Simeone Deary Design Group

Did you create this mostly on the mainland or did you have to bring it over from Oahu?

I made it on the mainland. There was a point where I shipped a ton of unassembled glass parts and metal hardware to Hawaii and I assembled what I call the branch ends here. I shipped them back to Kentucky and then when I got to Kentucky, I assembled them into the full five-and-a-half foot link. The branches ended up being just over five feet and each branch has 22 pieces of glass. I know there’s 1,456 pieces of glass on the whole piece and there’s 616 light bulbs. It took 18 months from the beginning of the design conversation until installation.

What were some of the learnings along the way?

The big innovation of the whole project was figuring out how I could wrap brass with hot glass and keep its structural integrity. All of the parts for the branches where the wiring goes are hollow, brass tubes that are off-the-shelf lighting parts. But what happens is when I wrap them in glass, it has a diamond texture to it that refracts light. It becomes really beautiful in that way, but the heat transfers from the glass to the metal and then I can bend and manipulate the metal. That’s what gives it the natural movement and it becomes something really special.

I used solid rods of brass, wrapping glass around those, and those became what I call the twigs and all the twigs got attached to the part. So all the hollow pieces and the light bulbs were hung individually, and then at the end, I went back and attached all the twigs. When I saw that work, I knew that that was it. One of the principles that I work with is, leave room for magic. What I really mean is don’t be too attached to a linear outcome because you’re not allowing for the potential of all of the amazing things that are on the sidelines. You don’t need to know exactly where you’re going to end up; you just have to have enough inspiration and motivation to keep going forward. This project was a lot like that in the beginning where I didn’t know what the end was going to be and then all of a sudden it was like, boom, this is really unique.

Can you talk about the inspiration behind your name for it?

I call it, “who hung the stars” because the first studio I worked on it had dark gray walls and I was often there really late at night. I remember hanging all the branches and I check them for the wiring and put in all the lightbulbs. Every time I put a light bulb in, it felt like I was putting a star in the sky. Plus, when you move back, they look like a star constellation.

How did it all come together during the installation process?

I drove everything down from Kentucky, took two assistants with me and basically we spent a week on scaffolding. We had to go through and work from the center out.

So we hung the 56 branches, went back and wired everything, and then we went through and put all the twigs in to finish it. And then we did a final adjustment of everything.

The suspension system on it is really cool because it has these clips that slide up and down and they lock. So I was able to hang all the branches and then go back and adjust their heights and the angle of it as well. That was a really fun thing on site where Lisa and Ilyse were there while I was on scaffolding with my two assistants and they’re walking around saying, “Lower! Higher! Lower!” Everyone had input along the way.

Working with the architects, we were able to put an inch of wood across the entire ceiling, which made it so that we could anchor anywhere we needed. At the beginning, we planned for the branches to come from the trunk initially. But, each branch weighs 17 pounds, so if you had 17 pounds times 56, you’re looking at a lot of weight. But 17 pounds with just two load bearing points on the ceiling is no problem at all. That’s when we switched to individual branches that hung down but had movement to where it looks like they intersect. That was one of the engineering things that was simple in theory, but was essential and very practical.